Updated 18 March 2025 at 15:22 IST

Mao Wanted Him Captured—How the Dalai Lama Outplayed the Chinese Army 65 Years Ago and Escaped the CCP

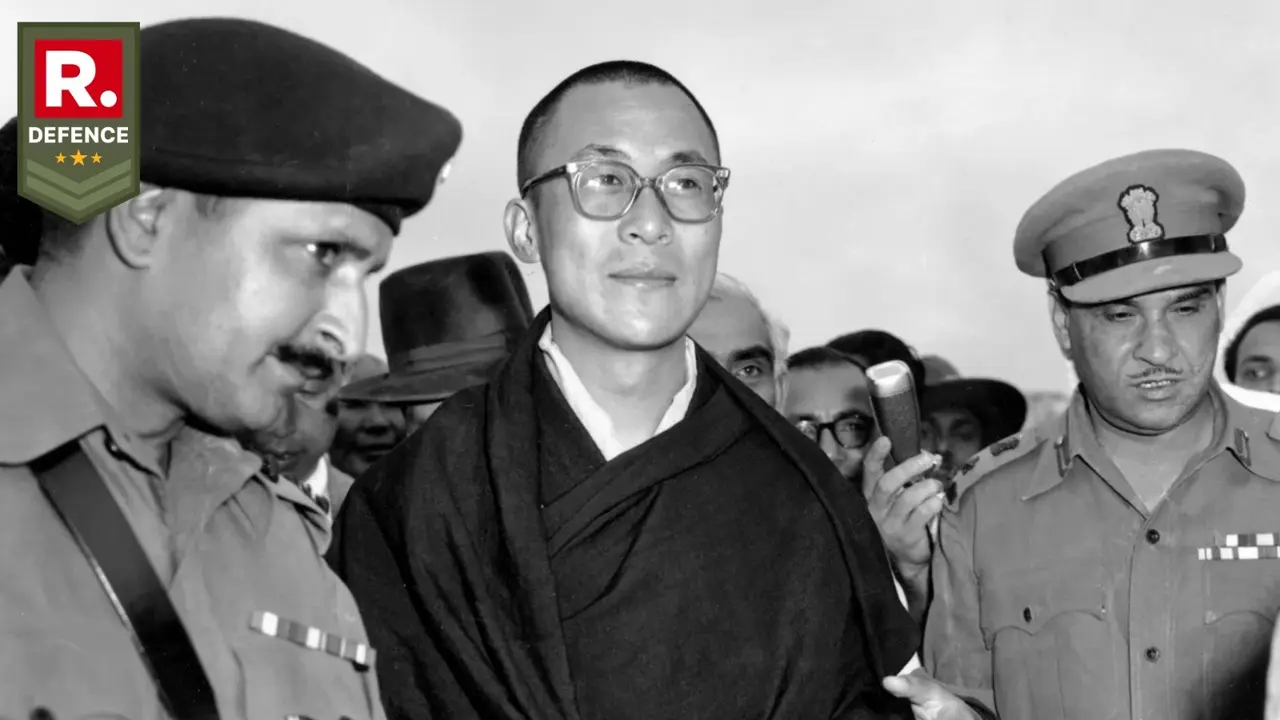

In March 1959, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, made a daring escape from Lhasa, Tibet, disguised as a soldier.

- Defence News

- 5 min read

Lhasa, Tibet – On a cold, tense night in March 1959, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, made a daring escape from Lhasa, Tibet, narrowly avoiding what could have been a Chinese-orchestrated abduction—or worse. Disguised as a common soldier, Tibet’s 23-year-old spiritual leader embarked on a harrowing journey through the Himalayas, pursued by Chinese forces that had already tightened their grip on the Tibetan capital. His flight was not just a personal bid for safety but a desperate act to preserve Tibetan identity, culture, and sovereignty—all of which were under systematic attack by the People’s Republic of China.

Beijing’s Betrayal: The Manufactured “Liberation” of Tibet

To understand the Dalai Lama’s escape, one must first understand the blatant betrayal of Tibet by Communist China. Following the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, Tibet declared itself an independent nation in 1913—a reality the world largely acknowledged, despite China’s reluctant denial. But the illusion of Tibetan self-rule was shattered in 1950, when Mao Zedong’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) invaded the region, claiming to bring “liberation” while actually launching an unprovoked military takeover.

The Seventeen Point Agreement, signed under duress in 1951, was nothing more than a thinly veiled surrender document. China promised Tibet “autonomy” but quickly reneged, stationing thousands of troops in Lhasa and eroding Tibetan governance, religious freedoms, and cultural practices. The so-called peaceful liberation turned into an outright occupation.

By the late 1950s, China’s rule had grown even more suffocating, with brutal crackdowns on Tibetan traditions and an aggressive push to Sinicize the region. Tibetan monks, the backbone of the country’s spiritual life, were persecuted and executed, while China tightened economic control, leaving Tibetans impoverished. This systematic cultural erosion set the stage for one of the most dramatic moments in Tibet’s history—the Dalai Lama’s escape.

Advertisement

The Uprising: Tibet Stands Its Ground

Tensions exploded on March 10, 1959, when the Dalai Lama received a suspicious invitation from Chinese General Zhang Jingwu. He was asked to attend a cultural performance at Chinese military headquarters—without his bodyguards. Tibetans immediately saw this for what it was: a trap. Fearing an attempted kidnapping or assassination, tens of thousands of Tibetans surrounded the Dalai Lama’s residence at Norbulingka Palace, forming a human shield to protect their leader.

The mass protests quickly turned into an armed uprising against Chinese occupation. Lhasa became a battlefield, with Tibetan resistance fighters engaging the PLA’s heavily armed forces. Beijing responded with brute force, shelling monasteries, homes, and protest sites. It was clear: if the Dalai Lama stayed, he would be captured or killed.

Advertisement

The Escape: A Race Against Death

On the night of March 17, 1959, as Chinese artillery fire echoed through the city, the Dalai Lama, now disguised as a Chinese soldier, slipped past his anxious followers and into the darkness. With a handful of trusted officials, family members, and bodyguards, he began a hazardous trek across the mountains, avoiding Chinese patrols, bitter cold, and treacherous terrain.

The journey to India was brutal. Travelling mostly at night, the group took refuge in monasteries and Khampa guerrilla camps, narrowly avoiding PLA search parties that scoured the mountains for Tibet’s fleeing leader. Every step was a risk—capture would mean certain imprisonment or execution at the hands of the Chinese regime.

Meanwhile, Beijing scrambled to control the international narrative, falsely claiming that the Dalai Lama had been abducted by Tibetan rebels. Mao Zedong himself was initially uncertain about the escape’s implications, contemplating whether allowing the Dalai Lama to leave could serve China’s interests. Ultimately, the Communist Party chose a different route: crush all Tibetan resistance and rewrite history to fit their agenda.

Safe in India, but Tibet Burns

On March 31, 1959, after two gruelling weeks, the Dalai Lama crossed into Arunachal Pradesh , welcomed by Indian authorities. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru granted him asylum, recognizing the gravity of China’s aggression in Tibet. The Dalai Lama eventually settled in Dharamshala, where he established the Tibetan Government-in-Exile—a move that infuriated Beijing.

As Tibet’s spiritual leader found safety, his homeland faced unimaginable brutality. The PLA launched a merciless crackdown, executing thousands, imprisoning monks, and destroying monasteries. The Tibetan resistance was crushed, and Tibet’s identity was systematically dismantled under the guise of Chinese “modernization”. The world largely watched in silence.

Decades of Repression, but the Fire Still Burns

More than six decades have passed since the Dalai Lama’s dramatic escape, but Tibet’s suffering continues. China has doubled down on its authoritarian grip, flooding Tibet with Han Chinese settlers, enforcing Mandarin education over the Tibetan language, and brutally suppressing any hint of resistance. Self-immolation protests by Tibetan monks have become a desperate cry for help—one that Beijing ignores and the international community often fails to act upon.

Despite this, the Dalai Lama’s escape remains a symbol of resilience. His unwavering advocacy for Tibet, despite exile, has kept the Tibetan cause alive. And while China boasts about its economic development projects in Tibet, it cannot erase the truth: Tibet was never voluntarily part of China, and its people continue to resist Communist rule in every way they can.

As Beijing tries to erase Tibetan identity, the memory of the Dalai Lama’s escape serves as a reminder of the lengths China will go to maintain control—and the strength of those who refuse to be silenced.

Published By : Yuvraj Tyagi

Published On: 18 March 2025 at 14:59 IST